The need to assess phonological processing when working with low progress readers

& Childhood Apraxia of Speech

When working with low progress readers, there are some who fail to respond to standard systematic phonics based intervention. Upon closer reading of the research, these students typically have weakness in both components of Phonological processing, the innate skills we are born with [as measured by Rapid Automatic Naming] as well as Phonological Awareness skills [which include both Phonological Awareness and Phonemic Awareness skills]. This combination of difficulties is consistent with the Double Deficit Hypothesis proposed by Maryanne Wolfe. Current intervention programs for this student population include RAVE-O [developed by Maryanne Wolfe] and Read3 [developed by Robyn Monaghan & Kate Andrews]

In my clinical experience, the students most at risk of presenting with a double deficit profile are those with a co-occurring diagnosis that may impact neurological functioning. Students I have worked with will typically have difficulties with RAN and PA skills alongside histories of epilepsy [Non-Rolandic Seizures], Traumatic Brain Injury, Severe Speech Sound Disorder, Childhood Apraxia of Speech, Rare Disease involving white matter damage in the cerebellum, Extreme Prematurity, significant family history of Dyslexia. Where these students presentment with co-occurring language impairment or DLD, intervention must be even more tailored towards individual student profiles of strength and weaknesses.

A recently published paper explores the Long-term Outcomes for students with CAS – including literacy outcomes. Key extracts from the paper are quoted below:

- Lewis, B.A., Miller, G.J., Iyengar, S.K Stein, C. & Benchek, P. (2023)., Long-Term Outcomes for Individuals With Childhood Apraxia of Speech Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research • 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_JSLHR-22-00647

‘The diagnostic criteria of childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) as a disorder of speech and motor planning and motor programming have been well studied since the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) published a report in 2007. ASHA defined CAS as “a neurological childhood (pediatric) speech sound disorder in which the precision and consistency of movement underly-ing speech are impaired in the absence of neuromuscular deficits (e.g., abnormal reflexes, abnormal tone)” (ASHA, 2007, pp. 3–4). Three core speech characteristics of CAS were used to define this disorder: error inconsistency, lengthened and disrupted co-articulation, and inappropriate prosody.’

There have been previous findings in the research regarding students with CAS and their literacy outcomes as detailed below:

‘The participants with CAS in the Snowling and Stackhouse (1983) and Stackhouse and Snowling (1992b) studies demonstrated persistent speech errors and comorbid literacy difficulties. The authors concluded that CAS arises from a complex interaction of phonological representations, lexical representations, and motor planning difficulties that also affect reading and spelling acquisition.’

‘Participants with CAS with impoverished linguistic abilities (i.e., oral language and phonological awareness) demonstrated below-average decoding skills, similar to below-average readers with other idiopathic SSD. In addition to oral language and phonological awareness, motor speech sequencing abilities, such as multisyllabic word repetition (MSW) and diadochokinetic rate, further differentiated average and below-average readers with CAS.’

‘Turner et al. (2019) examined speech, language, and literacy outcomes in a 15-year-old male diagnosed with CAS. By 15 years, he had acquired intelligible speech with average-range oral language skills; however, deficits in reading comprehension, decoding of nonsense words, and spelling persisted.’

‘One of the goals of this study was to examine the associations of persistent speech sound errors with word-level decoding, phonological processing skills, multisyllabic word repetition, and motor speech sequencing.’

‘However, regardless of persistence of speech errors, individuals with a history of CAS demonstrate an elevated risk of literacy difficulties. In this study, the persistent group did not differ significantly from the nonpersistent group on measures of single-word decoding or phonological awareness skills, often associated with literacy. Both groups were at similar risk for below-average decoding and phonological awareness. Many individuals with CAS present with phonological processing difficulties that may impact spoken language as well as literacy (Lewis et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2019; Miller & Lewis, 2022).’

‘Nathan et al. (2004) proposed that poorly specified phonological representations may underlie both speech errors and phonemic awareness. Other researchers proposed that the underlying phonological processing deficits may contribute to CAS itself (Marion et al., 1993; Marquardt et al., 2002; Stackhouse & Snowling, 1992a, 1992b).’

‘A larger second study of individuals with CAS (N = 40) enrolled in the CFSRS specifically examined reading outcomes compared to participants with other SSD (N = 119; Miller et al., 2019). Sixty-five percent of the participants with CAS, compared to 24% of those with other forms of SSD, were classified as low-proficiency readers based on single-word decoding of real and nonwords. Low proficiency readers in the CAS and SSD groups did not differ on measures of reading, language, or phonological awareness. Language and phonological awareness skills were the strongest predictors of reading skills.’

‘These findings suggest that although CAS is commonly defined as a motor speech disorder, SLPs should be aware of the comorbidity of language and literacy difficulties related to a diagnosis of CAS and design interventions accordingly (Gillon & Moriarty, 2007).’

‘Furthermore, the underlying deficit that results in reading disorder (RD) for children with CAS may differ from those with RD who have never had SSD. Miller and Lewis (2022) reported that although test scores of single-word decoding skills did not differ between these two groups, the CAS group performed significantly worse on measures of phonological processing, multisyllabic word repetition, diadochokinetic rates, and speech-in-noise per-ception. Those participants with CAS and language impairment (LI) were at the highest risk for deficits in literacy and literacy-related skills. If the causal basis for RD in children with CAS differs from children with RD and no Speech Sound Disorder, then interventions for garden variety RD may be less effective for children with CAS. More research is needed to specify the underlying deficits for reading difficulties of children with CAS and to develop interventions that address these issues.’

Research Recommendations [Lewis et al, 2023]

- Documenting early motor deficits may aid in improving prognoses and treatment for children with CAS.

- Identifying phonological processing deficits may result in earlier intervention for literacy skills.

- While speech sound production may normalize for some children with CAS, evidence from our studies suggests that literacy skills may remain impaired.

- For a child with a diagnosis of CAS, systematic preliteracy instruction could begin in preschool and literacy instruction by kindergarten (Zaretsky et al., 2010).

- It would seem unwise to remove children with an early diagnosis of CAS whose speech may normalize in the primary grades from an IEP if there is any evidence of phonological processing, language, or reading difficulties.

- These same children are at risk of being placed back on an IEP by the fourth or fifth grade because of learning issues, especially reading.

What to do next

Familiarise yourself with the research from Maryanne Wolf & team regarding Double Deficit Theory.

- Familiarise yourself with existing resources that can support students with weakness in phonological processing skills and learning to read

- Rave – O [Distributed in Australia by Silvereye Education]

- Read 3 [www.read3.com.au]

- Reading Dr Online which allows for a text to picture matching response rather than a read aloud response [www.readingdoctor.com.au]

- Consider adding assessment tools to your toolkit such as CHIPS [www.read3.com.au], CTOPP-2, WRMT-3 & RAN/RAS

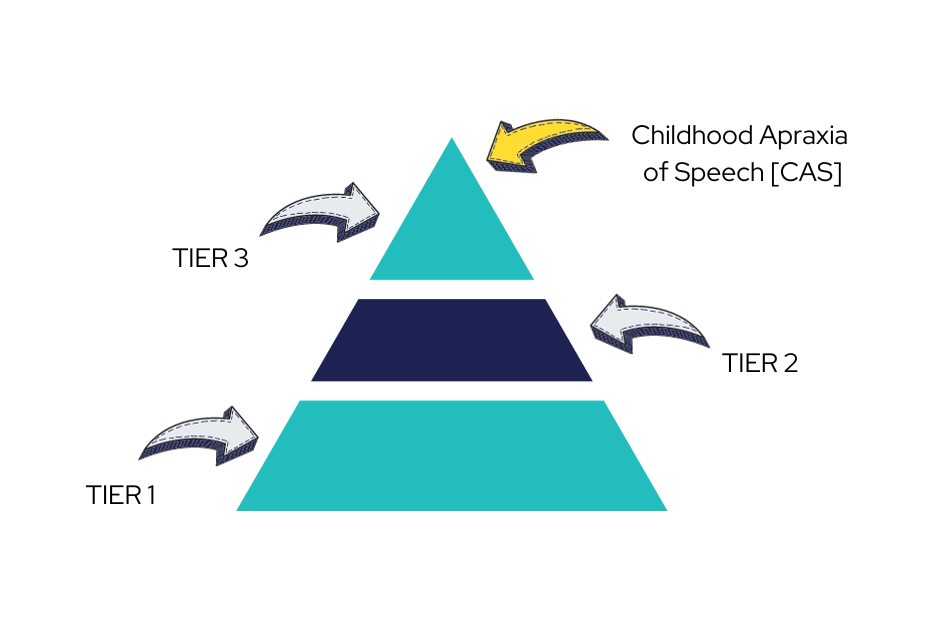

- If you need additional professional support and training join my Tier 3 Toolkit Membership for Language, Learning & Literacy. You can access an online library where we explore assessment tools, intervention resources and how to take a hypothesis driven approach when supporting reading, comprehension and writing skills for students requiring individualised Tier 3 supports and intervention in the clinic and classroom.

Reference:

Lewis, B.A., Miller, G.J., Iyengar, S.K Stein, C. & Benchek, P. (2023)., Long-Term Outcomes for Individuals With Childhood Apraxia of Speech Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research • 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_JSLHR-22-00647